Do you like love poems?

I confess I haven’t read many.

I read one by John Donne in college and I mostly stopped there; I guess my interest was satiated. In Donne’s “The Good Morrow,” nothing exists outside the lovers’ shared embrace. Nothing outside the beloved’s irises is even visible: “My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears…”

Well, it’s true that privacy makes obsession more profound. And sure, the eyes are the windows to the soul. It’s great to swim in the gaze of someone cute. But eventually you’ll have to step outside the boudoir and onto the sidewalk. Sometimes the object of one’s love is not secret but public, not singular but many. A love poem to the state is usually just propaganda, but what about a love poem to a city? It must go beyond what Donne calls “everywhere”—a single room.

That’s exactly the achievement of Curating Commemoration, the latest offering from the Providence Biennial for Contemporary Art. Apropos of the Biennial’s aspirations for an Art Basel-ish vibe en province, this year saw two curators charged with crafting two separate shows at the WaterFire Arts Center.

The exhibits grew in tandem, but are they compatible as roommates? Their transition is pretty smooth, if not seamless, thanks to their overlapping and deeper effort: Warbling out a love poem to Providence (or, if we’re being specific, its entire metro area).

Like any large-scale exhibition, the offerings are uneven, but this heterogeneity speaks to a ‘something for everyone’ appeal that suits a biennial presentation. I’ll readily admit I am not the ideal audience for everything on display, but there’s no ‘ideal’ audience anyway, and that’s by design.

“What would someone who isn’t Melaine want to see?”

That question guided Melaine Ferdinand-King as she assembled Poiesis, the Biennial’s larger serving with a roster 37 artists deep. As she explained in a curators’ talk on August 2, achieving that sizable list took a tireless grassroots approach, from open calls for submission to hours spent chatting in cafes, studios and restaurants. Such devotion needed a promise of equal measure, so Ferdinand-King excluded Providence artists who lacked love for their city, even if they were technically skilled.

“I went on a couple artist visits, to be transparent, and the works were amazing,” Ferdinand-King said. “There were landscapes, there were photographs, by artists who were based in or worked in Providence, but they didn’t love Providence. They felt like Providence didn’t really have much to offer as a creative capital; they don’t know what made it richer than a place like New York City or Boston. And so part of my selection wasn’t just about the artworks that you see but it was about the artists themselves and their personal stories…I wanted artists who would scream Providence from the rooftops."

Poiesis tangibly proceeds from this certain passion. It attempts a ground level survey of aesthetic subcultures, including those beyond the expected experiments of College Hill. A tufted map of Providence by the self-taught Sav Hazard-Chaney could be a synecdoche for the Biennial itself, or of Ferdinand-King’s curatorial vision. Rather than stubbornly promote certain tastes, she maps relations with thoughtful unions in mind.

Per the poet of relation himself, Édouard Glissant: “Relation is not made up of things that are foreign but of shared knowledge.”

The Us-Them distinction has long been a colonial one, and Ferdinand-King has plenty of knowledge to share contra this interpretation. There’s a rich tension in her curation that elevates the popular above both bourgeois and mass-mediated narrowings of art.

Photography, for instance, has always had a vernacular appeal totally detached from its artistic discourse. Ferdinand-King reconciles the two without destroying either. She includes plenty of photos, from straight documentary efforts to a series of collaborative portraits by Nyree Sylvia and Paige Huggon, where each model is rendered with a clarity so exquisite it feels like looking at an old friend.

Other standouts include Derek Raymond’s wheatpaste canvas, I WANT YOU TO LIVE (2021), which moved me more than I expected. The older I get, the more I appreciate a blunt sentiment represented bluntly. Mesmeric, meanwhile, is a music video by Julio E. Berroa, which animates the imagined landscape of “Providence 2043” for a chromatic, cyberpunk-y take on the city’s downtown and West End.

Contrasting Berroa’s holographic horizon is the earthy, rugged blue couture of designer Dorian Epps. Upcycled denim is donned by two mannequins with a royalty that feels not simply reused but more thrillingly usurped. Installed on an upright chest is the finishing touch: a custom hightop titled Bullsh*t (2021). I envied the chest for getting to wear it.

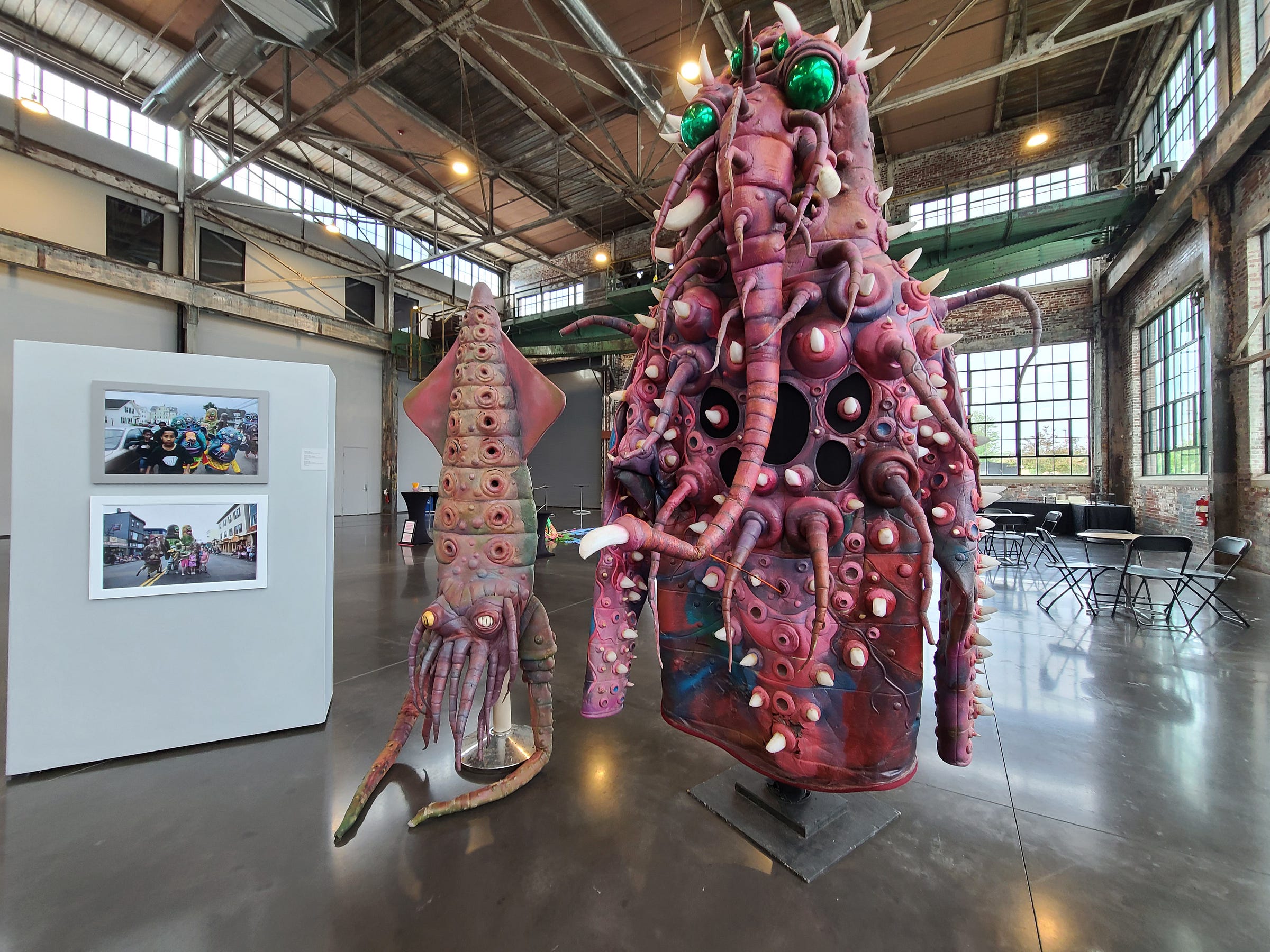

Maybe I just gravitated toward the teen boy aesthetics I never surrendered: animation, sneakers and ALL CAPS sentiment. Although, on the same youthful note, Ferdinand-King includes a kid favorite: the locally notorious alien menagerie of Big Nazo Lab. On display are photos and rubber puppets from their archives that go as far back as 2010.

Ferdinand-King had to advocate for Big Nazo’s inclusion against early concerns they might be too commonplace an addition. It’s true these creatures are often gallivanting around Providence, but they’re still less common than empties of Fireball, which litter probably every sidewalk in Providence if not America. Even more iconic than Big Nazo, these nips make a guest appearance in an installation by Isaiah ‘Prophet’ Raines.

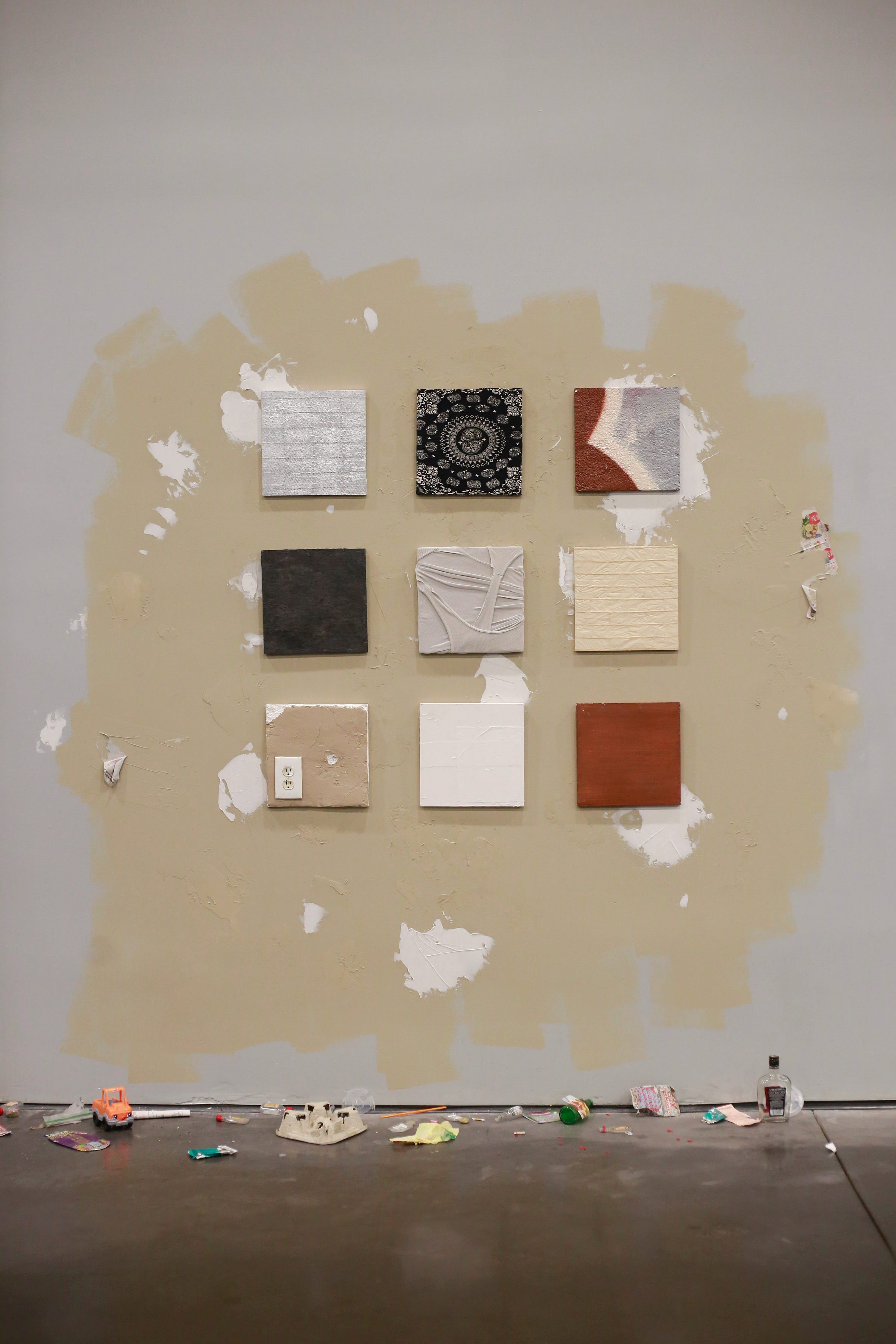

Raines’ 3x3 grid of wooden squares consists of everyday substances alchemized past immediate recognition: Gum wrappers. A black bandana and horsehair plaster. A “heavily worn White Wifebeater.” They’re all installed against a discolored patch of wall that looks fucked up, spackled over, with street trash strewn on the otherwise immaculate floor below. Raines inverts the logic of monumentality here. The city’s lived environment itself is restored to a place of tribute.

Per Raines’ artist statement: “I use my art as a means to retaliate against oppressors [and] negate the suffering of my people.”

The titles of Raines’ squares echo their counteroffensive intent: Burnt, Demolished, Indecent. Rag. Slumlord. Driving out abjection means subverting its own vocabulary. Rolling papers become something like a blanket. A tank top stretches with an athleticism beyond what any body could attain. An electrical outlet leads nowhere. Its power is not for the taking.

If Ferdinand-King works with “even the most mundane spaces,” then Joel Rosario Tapia pursues “the work of providing truth,”

per his statement for Remedy, the Biennial’s other half. With 11 artists, Remedy is a slimmer cohort with a leaner focus to match.

Édouard Glissant again: “[Colonization comprises] a tragic variation of a search for identity. For more than two centuries whole populations have had to assert their identity in opposition to the processes of identification or annihilation triggered by [colonial] invaders.”

Tapia’s medicine very much embodies this opposition. He casts an eye toward the long traumatic shadows of oppressors past, but his lookout is not a paranoid one. Tapia seems overall an optimist and not in the business of lament. He celebrates some of the identities that would otherwise be annihilated as Glissant describes, uplifting their “truth and realities.”

Lilly Manycolors’ mixed media canvases are literally lifted high: mounted in a wide array, they climb the wall well beyond eye level. Figures pose like archetypes amid symbols: a spider, an ear of corn. A snake and fresh flowers. A cosmic density, and also polka dots. With one piece measuring 13 feet wide, the scale of Manycolors’ works makes them feel properly spiritual—big enough to be a passage both backward and forward in time.

The work of Shey ‘Ri Acu’ Rivera Ríos also time travels, weaving through the futuristic and the earthbound. Even the ostensible hardness of cinder blocks receives tender affirmation in On Permanence and Mano de Obra (both 2022). On a gold-inked panorama, Rivera narrates a personal history while the cinder blocks sit stacked into a fortress of sorts below. Inside the concrete, artificial flowers function as colorful offerings—devotions that will last.

Frantz Fanon once wrote that “the muscles of the colonized are always tensed,” but the artists in Remedy detail eternities beyond this lockjaw. A red canvas by Savonnara Sok, The Lost and Found (2023), features two figures hugging not unlike John Donne’s lovers. Their warm caress is a freely-given endlessness.

Camaraderie and solidarity can emerge in any city,

but not everyone will fit in everywhere. Providence, as Ferdinand-King noted, has long been “weird” to its denizens’ own satisfaction. And refuges for the weird remain a minority. Tapia added that even before the Europeans landed, the region’s proximity to the shore made it highly sought after. As far as the two curators understand it, that hasn’t changed—PVD is as lively as ever, and getting livelier. A packed turnout on the exhibits’ opening night suggested as much.

“Providence is poppin,” Ferdinand-King said during the curators’ talk. The audience chuckled agreeably, but she adopted a matter-of-fact face and repeated: “Providence really is poppin.”

I went into this story thinking brevity or concision and I soon found myself flustered by the lyrical and the possible—just like walking around a few city blocks, sightseeing little bits of trash and circumstance.

Or as Tapia put it: every American city has its “slice of life” feel. Providence’s unique aura is something like a garden, he thinks.

I remember being 19 years-old and starting to see Providence through a similar generosity of atmosphere. I had a habit of pausing on the overpass near Broadway, listening to cars on the highway pavement below. Inside that sound, something clicked for this suburban odd duck: the city’s endless suggestion is life and more life yet. It brings into being that which wasn’t—which, by the way, is the meaning of ‘poiesis.’ The city changes people, and people change each other.

It wasn’t the flashiest revelation, but something more essential. Something like concrete.

I pledged ignorance about love poems, but here I am, writing one. I still think an exhibit works better. After all, some things are better seen in person. You should look someone in the eyes when you say you love them.

FYI: Curating Commemoration: Poiesis/Remedy is on view through August 20, 2023, at WaterFire Arts Center, 475 Valley Street, Providence, Rhode Island.

A closing celebration is slated for today, August 17, from 6-8 pm.

[*CHANGELOG: Edited 08.24.23 18:30: Clarified a quote from Ferdinand-King in second section, first graf.]